Vikings and Norse Gods in Iceland

Who were the early Viking settlers to reach Iceland’s shores, and who were the Gods that they worshipped? How is this Viking heritage still visible in Iceland today, and just why did the Icelanders choose to give up on their Pagan beliefs? Who were the most important Gods in the Norse Pantheon and how are they remembered today? Read on to find out all there is to know about Vikings and Norse Gods in Iceland.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, Carl Rasmussen. No edits made.

- Discover everything you need to know about the History of Reykjavík

- Read about The History of Iceland and get to know Iceland's Viking heritage

- Learn the answer to the question: Where Did Icelanders Come From?

Take just ten minutes to walk around Iceland’s picturesque capital city Reykjavík and, almost immediately, it will become clear that this little island was once home to the fiercest bracket of ancient warriors ever to have taken to the high seas. I speak, of course, about the Vikings.

More often than not, hotels and guesthouses will sport a logo portraying a thick-haired, horned-helmet wearing barbarian, whilst souvenir shops are awash with model longboats, fancy-dress costumes and toy axes.

Many tour providers choose to operate under the banner “Viking”—i.e. Adventure Vikings, Viking Heli-Skiing, Viking Horses—and even one of Iceland’s most famed beers is named after these free boating rovers. All of this alludes to a proud, violent and authentically Scandinavian period of history, a history the Icelanders seem quite content with glorifying.

Consider how this devotion goes even further. In downtown Reykjavík, there is a photo studio, Mink Viking Portraits, where guests can dress and take snapshots as these primitive berserkers. Only a short distance away, two institutions, the Settlement Exhibition and the Saga Museum are dedicated to explaining the ins and outs of Viking culture.

- See also: Top 9 Museums in Reykjavik

More to the point, the modern Icelandic male, apparently, has disavowed the grooming habits of twenty-first civilisation, instead choosing to sport a shaggy coat of facial hair worthy of Sweyn Forkbeard.

What’s often left unsaid, however, is that Icelanders were not actual Vikings themselves, at least not in regards to their behaviour. Instead, they were farmers and fisherman, the descendants of Danish and Norwegian Vikings who first voyaged to the island around 870 AD.

Once the Vikings arrived here, they tended to stay, making a quick end to the practice of raiding, raping and pillaging that had once made this warrior class so feared.

What did endure—at least for a short period of time—was the devotion to Norse Mythology, the deities of the North Germanic people from whom Icelanders sprang. Alongside that, the language spoken in Iceland has remained relatively unchanged from this early period; today, Icelandic resembles Old Norse so closely that contemporary students can still read the original Icelandic sagas in their native tongue.

Who Were The Vikings?

There are various theories as to where the term “Viking” originated; one looks to the feminine prefix ‘vík’, meaning ‘inlet’ or ‘bay’, while others claim the historic Norwegian settlement of Viken is where the name derives (hence, Vikings were the original “dwellers of Viken”).

- See also: What is an Icelander?

Alternatively, recognised etymologists such as Anatoly Liberman point to the Old Norse word ‘vika’, meaning ‘sea mile’, the space left between two rowing boats in convoy, while others refer to the 9th Century Anglo-Saxon poem, Widsith, which refers to Scandinavian pirates as “Wicings”.

Regardless, given the Scandinavians’ dominance of the sea during this early period, it wasn’t long until contrasting names were being offered up by various other cultures across the planet. The Arabs, Slavs and Byzantines, for example, knew of these raiders as ‘Rus'’ or ‘Rhōs’ (relating to ‘rowing’), while the Germans labelled them as Ascomanni ("Ashmen"), alluding to their ash wood boats.

Other nations such as the English and Celts settled merely on Danes, Heathens or Pagans, whilst the Irish referred to them as ‘Dubgail’ and ‘Finngail’ ( ‘dark’ and ‘fair foreigners’) or, quite suitably, ‘Northmen’.

Given the common cultural practice of tormenting coastal settlements and monasteries, it wasn’t long until the Viking’s fearsome reputation spread to almost all corners of Europe and Mesopotamia—there is even evidence that the Vikings reached Baghdad, the centre of the Islamic Empire at the time.

- See also: The Nature of Icelanders

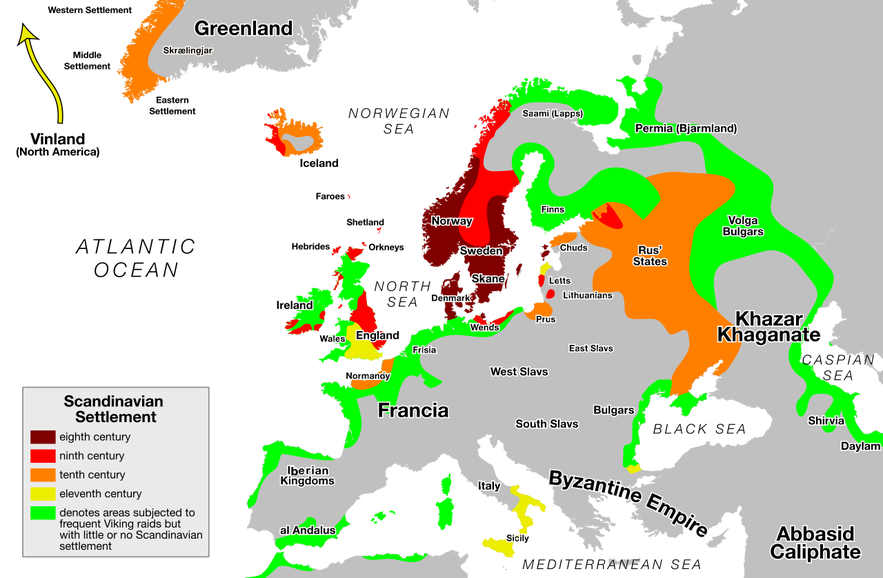

The Viking Age, as commonly referred to, lasted from the early 790s to the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. Throughout this period, the Vikings used the Northern and Baltic seas to terrorise neighbouring kingdoms, extending their influence through combat and culture until, eventually, Vikings could no longer be merely described as coastal raiders.

Consider the facts; two Viking kings, Sweyn Forkbeard and Cnut the Great, would ascend the English throne. Leif Erikson (an early Icelander) would settle short-lived colonies in North America. Scandinavians would even serve as mercenaries for the Byzantine Empire. In short, these were no mere pirates, but the forefathers of a patchwork-quilt culture.

The motivations for such expansion are subject to debate for modern historians, though there are clear incentives as to why the population of Scandinavia might have acted in the way that they did during this 200 year period. One relatively apparent reason is a scarcity of resources, thus forcing the Vikings to look further afield, even robbing and killing classes of people blessed with a more bountiful homeland.

- See also: The Most Infamous Icelanders in History

Another possible stimulus is the rule of Charlemagne and the religious persecution that went hand-in-hand with it. With Christian influence seeping ever further into Denmark, Sweden and Norway, it makes logical sense that the Vikings were looking to protect their pagan belief system, resist Judeo-Christian values and even take revenge for those settlements already lost to a monotheistic devotion. This is not speculation; the introduction of Christianity would come to divide Norway for almost half a century, causing untold bloodshed and cultural transformation.

It should also be noted that during the Viking Age, Scandinavia’s closest neighbours were experiencing varying levels of inner turmoil, thus granting the Vikings an advantage when exploiting these lands for wealth, slaves or territory. The sea routes used by the Vikings were almost entirely free of opposition, leaving the raiders unimpeded as they travelled from one destination of plunder to the next.

This breakdown in what had once been a profitable network of trade routes for European kingdoms can be heralded back as far as the collapse of the Roman Empire in the 5th Century, and later, to the rapid 7th Century expansion of Islamic philosophy.

The end of the Viking Age can be pinned down to a number of factors. First of all, the fallout that occurred following the Christianisation of Scandinavia would have untold effects on the region’s domestic and foreign policy.

By the 12th Century, Denmark, Norway and Sweden were effectively controlled by dioceses legitimised by the Catholic Church and had firmly established themselves as separate Kingdoms. This meant an enormous cultural shift in the priorities of Scandinavia’s leadership; in that sense, the Vikings were not defeated, but arguably, made to behave in a manner that fit the civility of their quickly transforming homelands.

For example, the medieval church made it forbidden to take fellow Christians as slaves. Given the fact that slave-trading was the number one source of profit for the Vikings, this removed a great deal of the economic incentive to travel and raid overseas. The new leadership also chose to refocus their military attention from the kingdoms of the west and, instead, partake in such campaigns as the Baltic Wars and the attempted conquest of Jerusalem.

From here on out, it seemed, the Vikings were no longer a recognised force in the world, though their brutality, bravery and strength would long be remembered by those who had once felt the sharp edge of their battleaxe.

Where Are The Norse Gods?

The Christianisation of Iceland occurred in the year 1000 AD, after the Pagan lawspeaker, Thorgeir Thorkelsson, decided to ratify the religion by law. This decision was taken after deliberating for a day and a night, culminating in the lawspeaker throwing his pagan idols into the now widely-visited tourist attraction, Goðafoss (“Waterfall of the Gods”).

- See also: Folklore in Iceland

His decision to fall upon the side of Christianity was largely twofold; first of all, Iceland was under the jurisdiction of Norway, a country whose King, Olaf Tryggvason, had converted in 998 AD. This led to the second major factor in the lawspeaker’s decision; the King’s conversion meant that many Icelanders decided that they too would convert, thus threatening a civil war in the country.

Thorgeir Thorkelsson’s decision to forgo his own beliefs was seen as a means of avoiding said violence, with the stipulation added that Icelanders were still free to worship the Norse Gods, as long as it was undertaken in secret. This would eventually be made illegal but implies the strength of conviction that many Icelanders of the time had in the Gods of Norse mythology.

In practice, upon the Church taking full ecclesiastical and judicial control, sweeping changes occurred across the country with such acts as infanticide and the eating of horse meat being banned by law—definitely two of the better decisions made in the name of a Christian God.

Today, Iceland is still considered to be a Christian country, but the mythological remnants, both physical and alive in the Icelandic psyche, continue to demonstrate their power, influence and historical relevance across many aspects of Icelandic culture.

Who Were The Norse Gods?

What we as a contemporary culture know of the Pantheon of Norse Gods can be found almost exclusively in the Icelandic sagas, written records of the oral tradition that spanned back to the Germanic tribes of Scandinavia.

Of particular relevance is the 13th Century manuscript, Prose Edda—written by one of Iceland’s most famous poets and scholars, Snorri Sturluson—and the earlier Poetic Edda, a collection of songs, stories and poems written by numerous authors.

Both sources are excellent examples of euhemerism, a word that describes the process of how actual historical events begin to be communicated as mythological tales.

- See also: A Guide to Icelandic Runes

According to these early works, humans and deities alike are said to have been magic-wielding and capable of supernatural feats, such as being able to transcend the Nine Worlds of Norse Mythology, such as Asgard, home to the Æsir (the principal pantheon of deities). These Nine Worlds, as listed below (with relevant links to more information), are unified by the world tree, Yggdrasil.

- Asgard.

- Álfheimr/Ljósálfheimr.

- Niðavellir/Svartálfaheimr.

- Midgard (Earth).

- Jötunheimr/Útgarðr.

- Vanaheimr.

- Niflheim.

- Muspelheim.

- Hel (Heimr).

In a relatively short article, it is all but impossible to list the many thousands of deities, giants, mischievous spirits, elves and monsters that illuminate the pages of these early works, as well as the sagas that followed.

- See also: Icelandic Literature For Beginners

However, given the lasting legacy of so many of them—as well as the collective and longstanding interest in Marvel superheroes—some of these Norse Gods are still very much alive in the collective imagination. Below, is a list of some of the most important deities and characters to the pre-Christian population of Iceland.

Odin

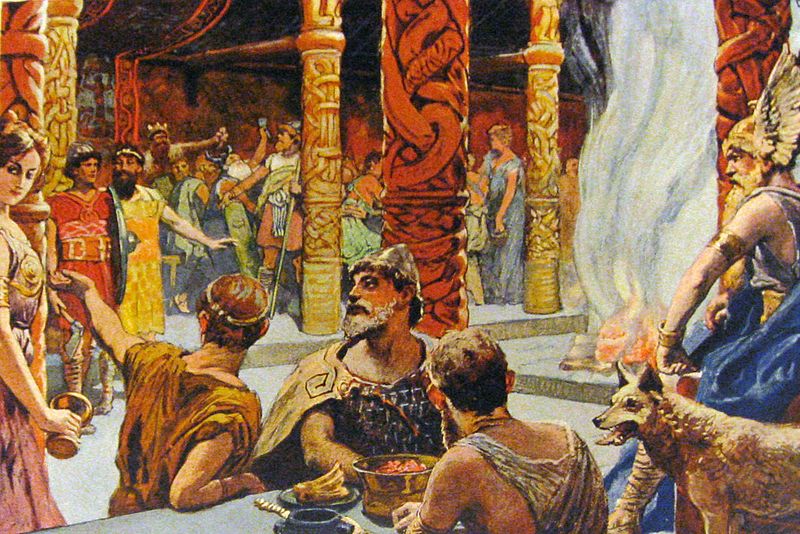

Otherwise known as Alfadir or ‘Allfather’, Odin is indeed the father of the Gods, the chief divinity found in Norse Mythology. Acting as both the God of War and Death and the God of Poetry and Wisdom, Odin is able to watch over all of the Nine Worlds from his throne in Valhalla.

Unlike the deities of later traditions, Odin’s stories imply the unworthiness of omnipotence in Norse mythology; sacrifice, selflessness and the constant quest for knowledge are all important aspects of his character. This point is made most famously in the tale of how Odin lost his eye in exchange for a sip of enchanted water, from which just a mouthful would grant him wisdom and foresight.

- See also: The Story of Icelandic Cinema

Today, Odin’s legacy is still felt every single week, on Wednesday, originally named as ‘Wodin’, or ‘Odin’s Day’. Visitors to Ásbyrgi Canyon in Iceland will also see the ‘geological imprint’ of Odin’s great eight-legged horse, Sleipnir, when he placed a hoof onto the earth, thus creating this dramatic natural feature.

Thor

Aside from having lent his name, quite obviously, to Thursday, Thor is the red-haired God of Thunder, famed for his magical hammer, Mjollnir, and his strength-doubling belt, Megingjörð.

Historically, Thor was the most popular of the all of the Norse deities; this was due to his placement as protector of both Gods and humans. Eventually, his popularity outranked that even of his father, Odin, because unlike him, he did not require human sacrifice.

The Romans knew of Thor as Jupiter, whilst the Germanic tribe, the Teutons, knew of him as Donor. Regardless of whatever name Thor went by, his stellar reputation for power and justness were felt wherever stories of him were told. According to the sagas, the Norse believed that, during a thunderstorm, Thor was riding across the heavens in his chariot.

Loki

Loki the Trickster; one of the most famed, dangerous, intelligent and beloved anti-heroes to have ever held a place, not just in Norse mythology, but in all of the world’s religions, historic and contemporary.

Tales of Loki’s mischief, mayhem and overall amoral outlook on the universe won him respect and condemnation in equal measure, not just among the human world that worshipped him, but so too amongst the Gods in which he surrounded himself.

Despite his ethereal position, Loki is, in fact, not a God himself, but instead, the son of two giants (the mortal enemies of the Æsir). Using his malevolent cunning, Loki was known to drag Gods, people and animals into a spider’s web of complicated problems, only offering them a solution once he had taken enough pleasure in their misery.

- See also: Witchcraft and Sorcery in Iceland

To highlight his importance to the stories of Norse mythology, it is Loki who is responsible for the eventual downfall of the Gods, setting in the motion Ragnarök, aka; “the end of the world”/”Fate of the Gods”, and thus signifying how nothing, not even the Gods, can ever remain static.

This duality—this good vs. evil symbolism—is what makes Loki one of the most interesting characters in folklore; after all, how often is it in the religious sphere that we find ourselves often siding with the blatant antagonist?

Baldr

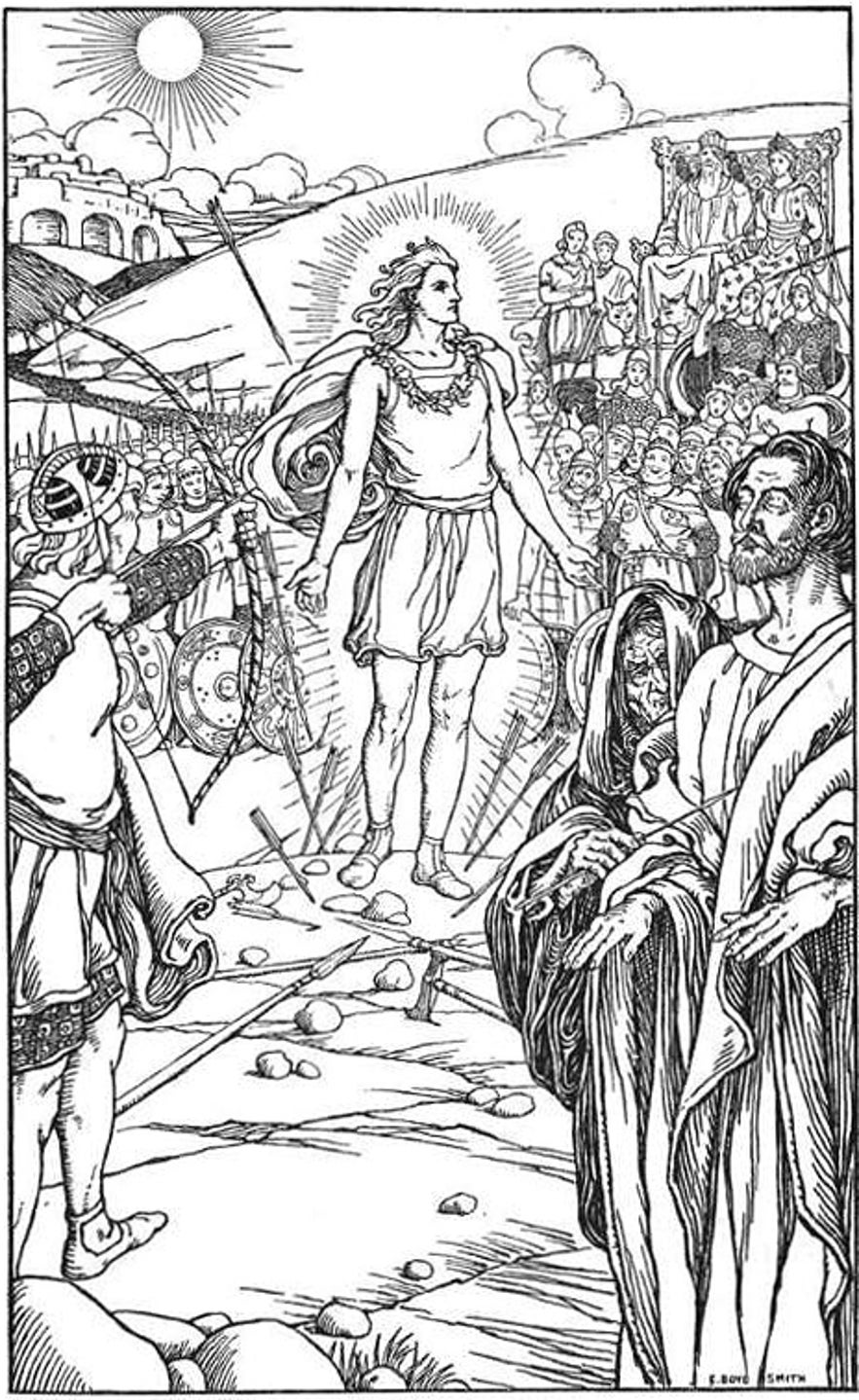

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Elmer Boyd Smith. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Elmer Boyd Smith. No edits made.

Baldr the Brave is the son of Odin and known as the God of Light, Innocence, Resurrection and Beauty. Though not as powerful as many of the other Gods in the pantheon, his reputation for integrity and friendliness made him beloved among worshippers and deities alike.

Unfortunately, Baldr is most famous for his death, a death that occurs—for all means and purposes—at the hands of the trickster, Loki. Having been dreaming of his death, Baldr’s mother, Frigg, made every living creature, big and small, commit to an oath that they would never harm Baldr. Feeling satisfied that he was now invincible, the other Gods would use him for target practice when throwing spears and arrows.

Unfortunately, Baldr still held one Achilles heel; a mistletoe dart. Utilising his shapeshifting abilities, Loki travelled to collect this mistletoe dart, then handed it Baldr’s blind twin brother, Hod, to throw at him. When this occurred, Baldr fell dead and Asgard fell into mourning. This would be the first act that led to Ragnarök and symbolises a loss of innocence among the Norse Pantheon.

Frigg

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Carl Emil Doepler. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Carl Emil Doepler. No edits made.

Frigg is the Goddess of Marriage, Fertility and Love; as Odin’s wife, she is one of the most recognisable goddesses in Norse mythology.

Historically, pagans worshipped Frigg at times of childbirth in the hope that their prayers would give both the child and mother good health and safe passage during childbirth. They also chose Frigg as their primary deity of worship when undertaking domestic work, or producing arts and handicrafts. In illustrations, this is often symbolised by Frigg sitting at a spinning wheel.

Frigg is remembered as having lent her name to the weekday ‘Friday.’ With Odin, her children included Freya (whom many believe is Frigg in another form) and Baldr, who is later killed.

Did you enjoy our article about Vikings and Norse Gods in Iceland? What did you find most interesting about Viking and Pagan history during your stay in the country? Make sure to leave your thoughts and queries in the Facebook comments box below.

Other interesting articles

Rivers for Sale | The Future of Iceland's Water Systems

Contrary to popular belief, the majority of Iceland's power production is not geothermal but hydroelectric. Plans are now in motion for eight new hydroelectric power plants that will dam the country...Read more6 Facts You Didn't Know About Icelandic Water

What role does water play in Icelandic culture and society? What is the secret behind the international reputation of Icelandic water? Can visitors drink from the tap in Iceland? How do Icelanders u...Read moreNew Year's Eve in Iceland

What is New Year's Eve in Iceland like? What is New Year's Eve in Reykjavik like? What makes New Year's in Iceland special? Where are the best parties in Reykjavik on New Year's Eve? Learn all this...Read more

Download Iceland’s biggest travel marketplace to your phone to manage your entire trip in one place

Scan this QR code with your phone camera and press the link that appears to add Iceland’s biggest travel marketplace into your pocket. Enter your phone number or email address to receive an SMS or email with the download link.